Sprites, elves, trolls, and pixies.

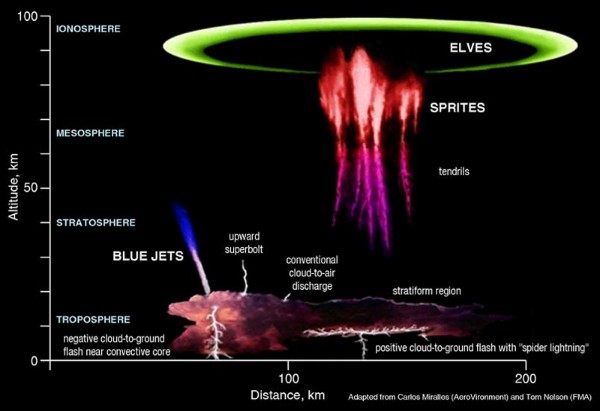

No, we’re not talking fairy-tale creatures. Sprites, elves, trolls, and pixies are all types of transient luminous events (TLEs)—bursts of red and blue light that occur high above thunderclouds and last for as little as a fraction of a second.

Named for their fleeting nature, eyewitness reports of strange flashes above thunderstorms were reported for more than a century before scientists accidentally caught one on film during a test for a rocket mission in 1989. Since then, scientific campaigns have captured stills and high-speed recordings of sprites and other TLEs around the world.

Scientists have many unanswered questions about the phenomena, said Burcu Kosar, a space physicist from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Centre. Kosar is leading Spritacular, a community effort to build the first global database of sprites and other TLEs for scientific study.

“We need more observations to understand various aspects of sprites and other transient luminous events,” said Kosar. “We may even find new types.”

It’s an electrical zoo up there.

Characteristic examples of sprites include carrots, which look like bunches pulled right out of the garden, and jellyfish with dangling tendrils.

Sprites are generally hidden from view, occurring at an altitude of roughly 80 kilometres. “Electrical activity affects the atmosphere above [the storm], creating various optical phenomena—it’s an electrical zoo up there,” said Kosar, who will introduced Spritacular on 16 December at AGU’s Fall Meeting 2022.

Whereas scientific efforts to document sprites have declined recently, Kosar said, amateur sky watchers known as “sprite chasers” have been sharing photos of them online for years. The largest group of sprite chasers, the International Observers of Upper-Atmospheric Electric Phenomena, started in 2013 and now has more than 7,000 members.

“Their photos are fantastic,” said Kosar, but “other than a few researchers, the science community is largely unaware of their efforts and observations.”

Kosar, who was previously involved in an aurora-spotting crowdsourced science project, saw an opportunity to create a community where weather photographers and scientists could collaborate. The data and images collected by Spritacular will be used by scientists for new and ongoing research into TLEs.

Knowing where to look

Kosar recently had her first sprite-chasing experience with weather photographer Paul Smith in Oklahoma. “We were out night after night scouring the skies,” she said.