On July 9 1962 at 09:00:09 Coordinated Universal Time UCT, the Starfish Prime test was detonated at an altitude of 400 km above the earth. The coordinates of the detonation were 16°28′N 169°38′W / 16.467°N 169.633°W. The actual weapon yield came very close to the design yield, which various sources have set at different values in the range of 1.4 to 1.45 Mt (5.9 to 6.1 PJ). The nuclear warhead detonated 13 minutes 41 seconds after lift-off of the Thor missile from Johnston Atoll.

Starfish Prime essentially created an artificial solar storm complete with auroras, geomagnetic activity and blackouts. Much of the chaos that night was caused by the electromagnetic pulse (EMP), a ferocious burst of radiation that can ionise the atmosphere and pepper the ground below with secondary particles akin to cosmic rays. Government and industry researchers have been studying the Starfish Prime EMP for decades.

A new paper recently published in the research journal Earth and Space Science suggests they might be overlooking something. “Typical EMP simulations found in government and industry reports use over-simplified models of the Earth,” says lead author Jeffrey Love of the United States Geological Survey. “They do not provide accurate estimates of the hazard in complex geological settings.”

In their paper, Love et al describe how a high-altitude nuclear blast jerks Earth’s magnetic field. First, the EMP ionises a layer of air underneath the bomb. This layer presses downward, pinning Earth’s magnetic field lines in their pre-blast locations. Next, as the ionisation subsides, the magnetic field springs back. It’s a sort of heaving, lurching geomagnetic storm.

Geomagnetic storms are famous for causing power blackouts. Usually the sun is to blame, but EMPs can do it, too. Lurching magnetic fields cause electrical currents to flow through the ground. Literally, rocks beneath your feet begin to tingle with electricity. These currents, in turn, make their way into grounded electric power grids, potentially damaging transformers and blacking out power supplies.

The crucial point of Love’s paper is this: Earth is not the same everywhere. In recent years, researchers have been sounding Earth’s crust to determine the 3D electrical properties of our planet. These magneto-telluric surveys reveal huge variations in conductivity from place to place, depending on the mix of underlying rock.

Love has been one of the pioneers in applying this type of Earth data to space weather, predicting how global geomagnetic storms might affect local power lines. Now he and his colleagues are doing the same with EMPs.

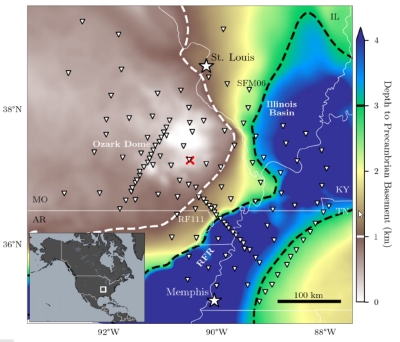

The team focused their attention on the eastern midcontinental USA, a region bracketed by St. Louis, Missouri, and Memphis, Tennessee. Between 2016 and 2019, the USGS conducted a magneto-telluric survey of the area, so the data is fresh. The terrain is remarkable for its mix of rock types. Underneath it all is a layer of Precambrian basement rock, which is electrically resistive; this is overlain by differing depths of younger, electrically conductive sedimentary rock. Notable features include the Ozark Dome, where the sedimentary layer is thin, and the Reelfoot Rift, which is deeply filled with sedimentary rock.

Love’s team simulated a nuclear explosion about 300 km above this region. They found a huge range of geo-electric responses. Some power lines in the simulation had excess voltages near 2000 V, while others were closer to 0 V. Both were sharp departures from previous studies.

“Given the results of our analysis for the eastern Midcontinent, it is reasonable to envisage performing similar analyses for other places,” the authors conclude. A geophysicist’s work is never done!

References: Dr Tony Philips, Spaceweather.com