"Our sensors measured a significant change in atmospheric electricity," reports Prof. Gang Li, a space physicist at the University of Alabama. "Earth's entire global electrical circuit was affected by the storm."

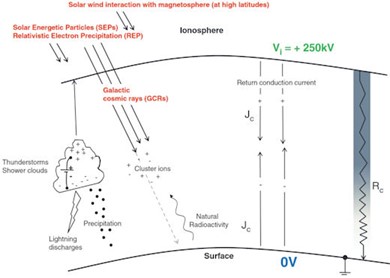

Earth has a "global electrical circuit." It is created by thunderstorms, which build up a charge difference between the ground and the ionosphere 50 km overhead. There are about 40 000 thunderstorms per day all over the Earth. We can think of them as batteries pumping the electricity to the top of the atmosphere. The resulting voltage drop is a staggering 250 000 volts.

On its own, air is not a great conductor of electricity. However, cosmic rays from deep space ionize our atmosphere, creating just enough conductivity for currents to flow in response to those 250 000 volts. The very air we breathe is thus electrified.

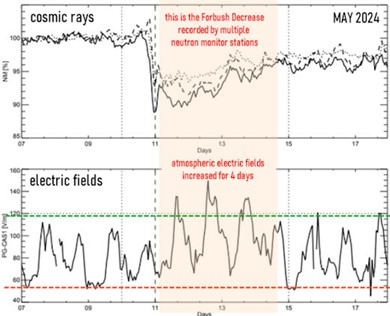

In April 2024, Li and colleagues published a paper in the journal Space Weather about solar storms and the global electric circuit. They described how CMEs approaching Earth sweep aside cosmic rays, decreasing their intensity. This is called a "Forbush Decrease," named after American physicist Scott Forbush who studied cosmic rays in the early 20th century. During a Forbush Decrease, fewer cosmic rays are available to ionize Earth's atmosphere changing the conductivity of the entire global electrical circuit. Li's team found that large Forbush Decreases boosted electric fields in the atmosphere.

The CME that hit Earth on 10 May 2024, caused a very large Forbush Decrease.

Li and colleagues checked two electric field monitoring stations at the CASLEO observatory in Argentina--a site they often used to monitor the global electrical circuit. During the May 10 superstorm, electric fields jumped 10% to 15%, an increase that lasted for more than four days. "This is in good accord with what we would have predicted based on our paper," Li said. Such changes in atmospheric electricity can affect many things ranging from the probability of rain and lightning to the flight paths of ballooning spiders, which ride electric fields through the air. Indeed, arachnids may have known of this phenomenon all along, but humans are only learning about it now.